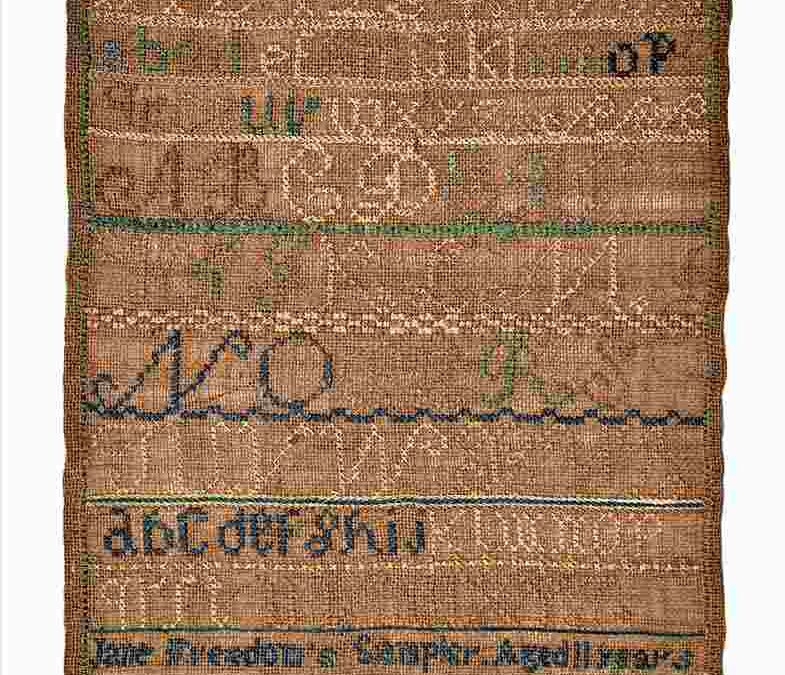

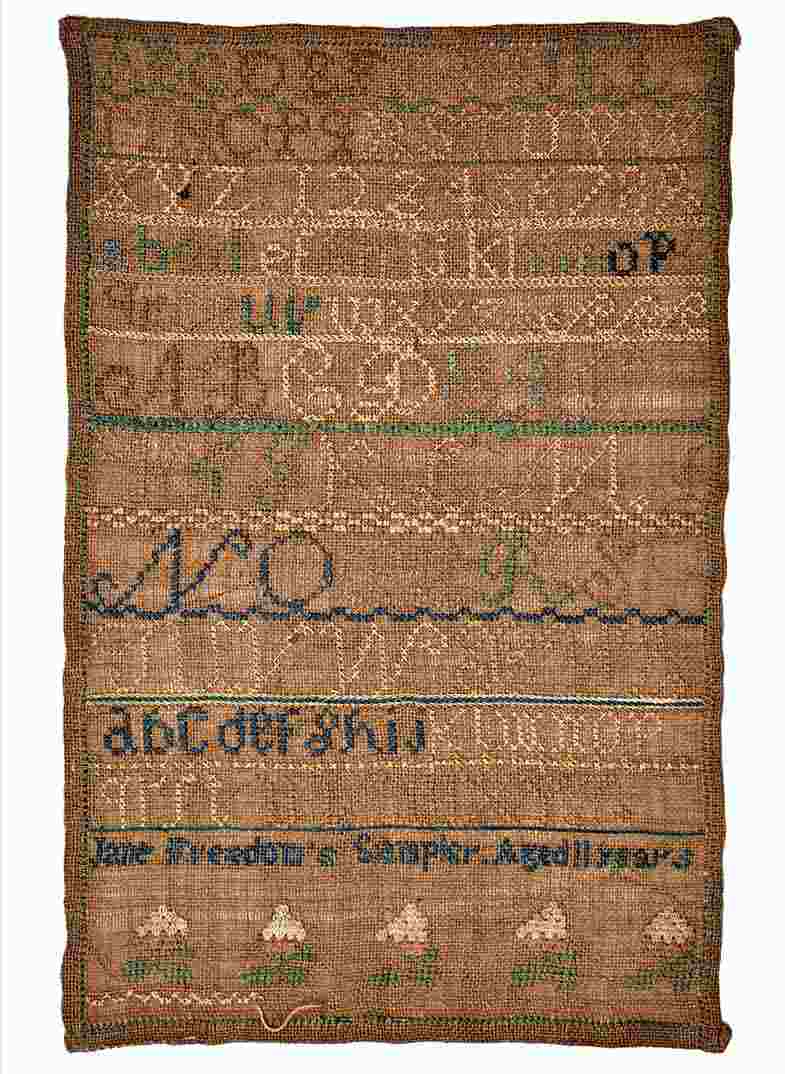

| Maker | Jane Freedom |

| Date of Creation | c. 1830 |

| Location | Norfolk, Litchfield County, Connecticut |

| Materials | Silk on linen |

| Institution | The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston |

| Credit Line | The Bayou Bend Collection, museum purchase funded by the Bayou Bend Docent Organization Endowment Fund |

| Accession Number | B.2023.9 |

| Photo Credit | Museum of Fine Arts, Houston |

This linen textile, embroidered with colorful silk, displays four decorative alphabets, the numbers 1–9, stylized strawberries, and the inscription “Jane Freedom’s Sampler. Aged 11 years.” Jane Freedom (1819–35), a young Black girl from Norfolk, CT, embroidered her name on this sampler in c. 1830. Her grandfather, Dolphin Freedom, chose the surname upon gaining his legal freedom. His son, Peter Freedom, passed it on to his children, including Jane. She died at 16, just five years after stitching her sampler, which then passed to her extended family. Her name, “Freedom,” and achievements imbue the object with signifiers of her skill, participation in local tradition, and selfhood. Samplers were fixtures of 19th-century girls’ education, but for Black girls in 1830s Connecticut—and the United States at large—learning was transgressive. Prudence Crandall’s 1832 attempt to open her Connecticut boarding school to Black girls was halted by mob violence and state legislation. It is thus unlikely Jane Freedom studied at the prestigious boarding schools available to White girls; her education was likely local. This is substantiated by two Norfolk samplers with similar colors and styles and identical strawberries: Elizabeth Cone’s, c. 1826, and Anna Battell’s, c. 1825. Both girls were White. These three samplers suggest a local needlework tradition in 1820s–30s Norfolk in which White and Black girls meaningfully participated. Samplers have many purposes. They could hone intellectual skills, like literacy, or household skills, like labelling linens. They could signify girls’ femininity, marriage potential, and family refinement. They could beautify homes. Today, samplers evince the personal lives, creative agency, and selfhood of girls—especially Black girls—who are often erased, excluded, and silenced. This may be best expressed by girls stitching their own names, an act perhaps even more meaningful, especially in a nation that condoned slavery, for a girl named “Freedom.”